Most epithelial tissues are essentially large sheets of cells covering all the surfaces of the body exposed to the outside world and lining the outside of organs. Epithelium also forms much of the glandular tissue of the body. Skin is not the only area of the body exposed to the outside. Other areas include the airways, the digestive tract, as well as the urinary and reproductive systems, all of which are lined by an epithelium. Hollow organs and body cavities that do not connect to the exterior of the body, which includes, blood vessels and serous membranes, are lined by endothelium (plural = endothelia), which is a type of epithelium.

Epithelial cells derive from all three major embryonic layers. The epithelia lining the skin, parts of the mouth and nose, and the anus develop from the ectoderm. Cells lining the airways and most of the digestive system originate in the endoderm. The epithelium that lines vessels in the lymphatic and cardiovascular system derives from the mesoderm and is called an endothelium.

All epithelia share some important structural and functional features. This tissue is highly cellular, with little or no extracellular material present between cells. Adjoining cells form a specialized intercellular connection between their cell membranes called a cell junction. The epithelial cells exhibit polarity with differences in structure and function between the exposed or apical facing surface of the cell and the basal surface close to the underlying body structures. The basal lamina, a mixture of glycoproteins and collagen, provides an attachment site for the epithelium, separating it from underlying connective tissue. The basal lamina attaches to a reticular lamina, which is secreted by the underlying connective tissue, forming a basement membrane that helps hold it all together.

Epithelial tissues are nearly completely avascular. For instance, no blood vessels cross the basement membrane to enter the tissue, and nutrients must come by diffusion or absorption from underlying tissues or the surface. Many epithelial tissues are capable of rapidly replacing damaged and dead cells. Sloughing off of damaged or dead cells is a characteristic of surface epithelium and allows our airways and digestive tracts to rapidly replace damaged cells with new cells.

Generalized Functions of Epithelial Tissue

Epithelial tissues provide the body’s first line of protection from physical, chemical, and biological wear and tear. The cells of an epithelium act as gatekeepers of the body controlling permeability and allowing selective transfer of materials across a physical barrier. All substances that enter the body must cross an epithelium. Some epithelia often include structural features that allow the selective transport of molecules and ions across their cell membranes.

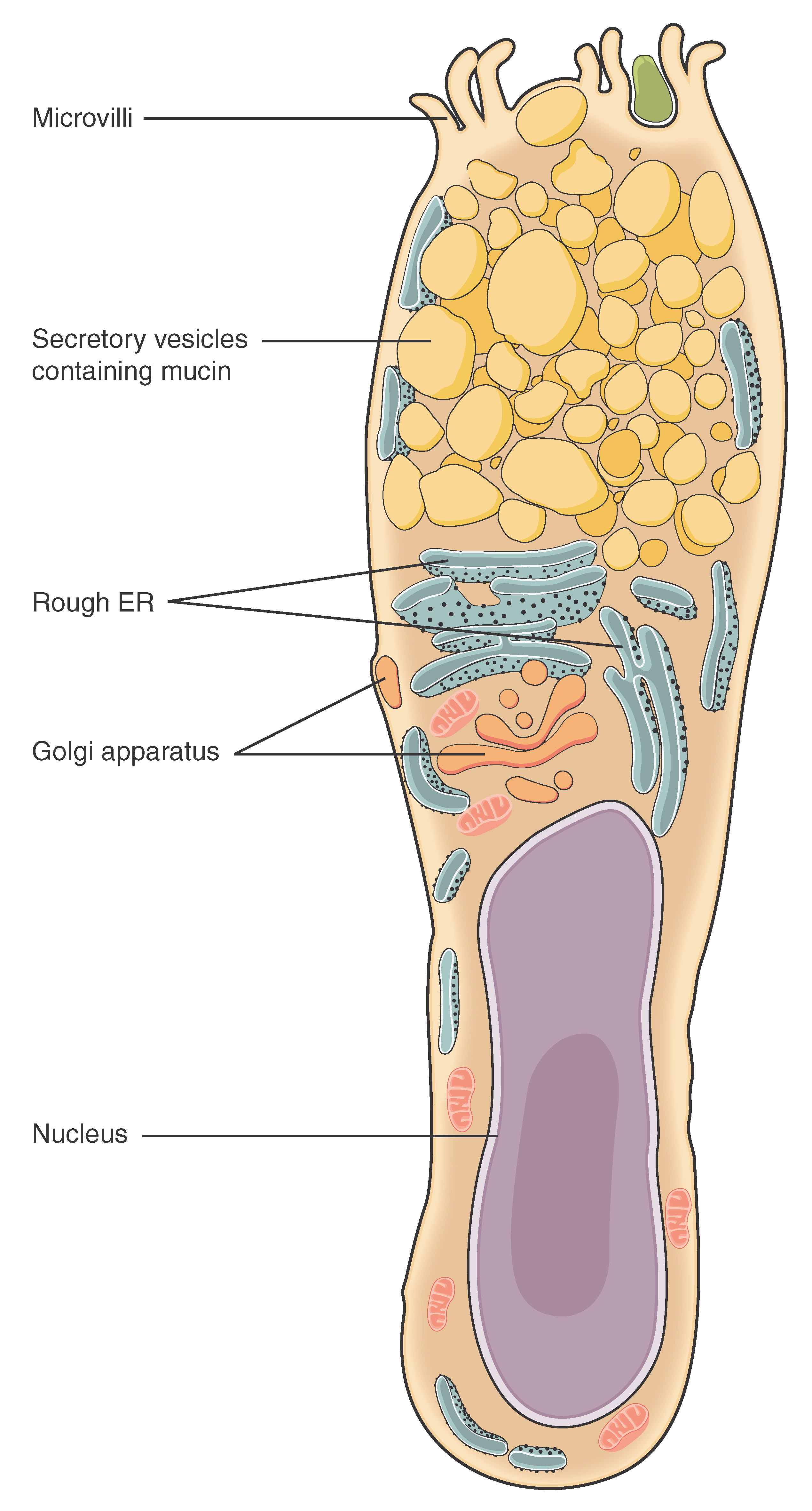

Many epithelial cells are capable of secretion and release mucous and specific chemical compounds onto their apical surfaces. The epithelium of the small intestine releases digestive enzymes, for example. Cells lining the respiratory tract secrete mucous that traps incoming microorganisms and particles. A glandular epithelium contains many secretory cells.

The Epithelial Cell

Epithelial cells are typically characterized by the polarized distribution of organelles and membrane-bound proteins between their basal and apical surfaces. Particular structures found in some epithelial cells are an adaptation to specific functions. Certain organelles are segregated to the basal sides, whereas other organelles and extensions, such as cilia, when present, are on the apical surface.

Cilia are microscopic extensions of the apical cell membrane that are supported by microtubules. They beat in unison and move fluids as well as trapped particles. Ciliated epithelium lines the ventricles of the brain where it helps circulate the cerebrospinal fluid. The ciliated epithelium of your airway forms a mucociliary escalator that sweeps particles of dust and pathogens trapped in the secreted mucous toward the throat. It is called an escalator because it continuously pushes mucous with trapped particles upward. In contrast, nasal cilia sweep the mucous blanket down towards your throat. In both cases, the transported materials are usually swallowed, and end up in the acidic environment of your stomach.

Cell to Cell Junctions

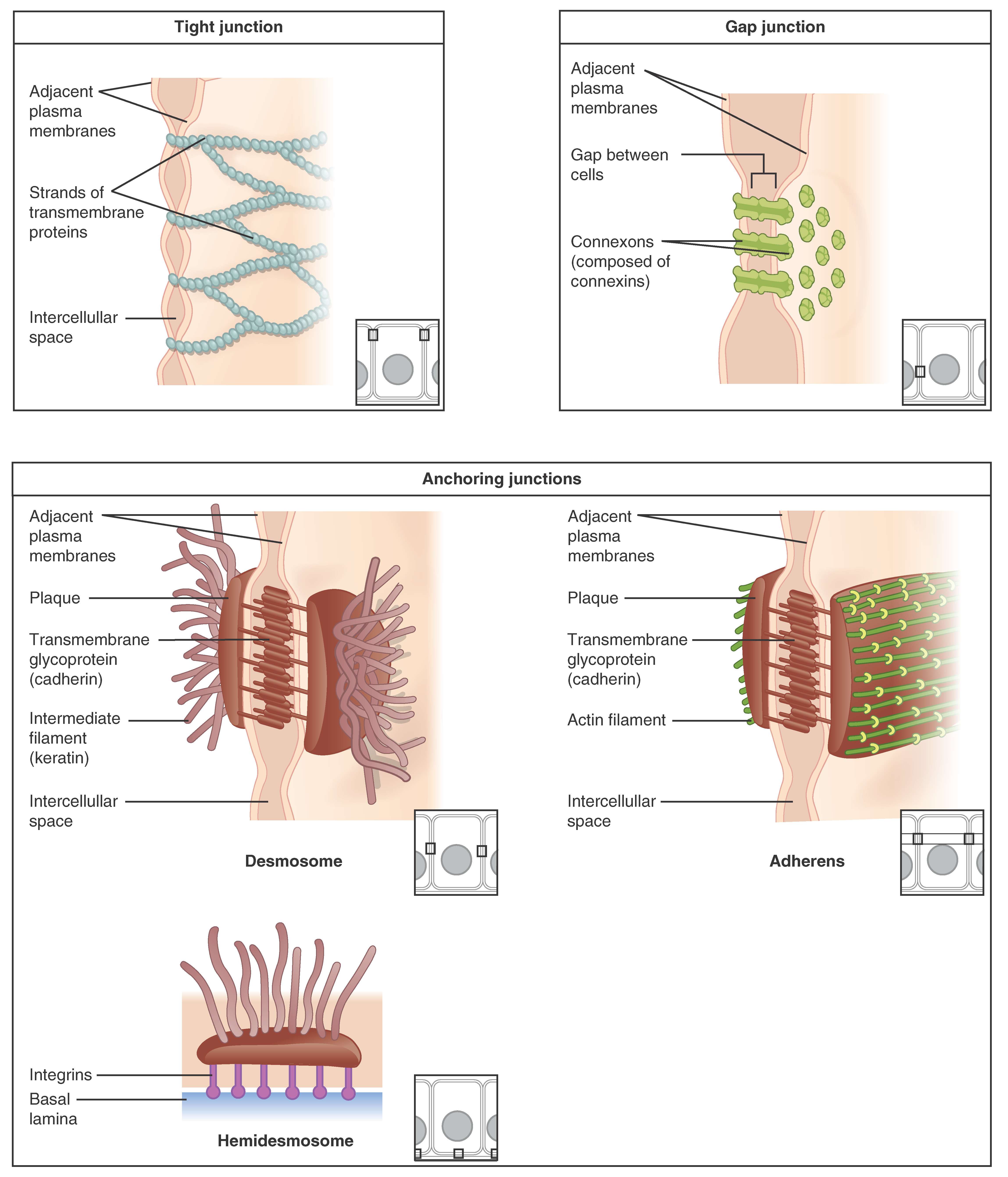

Cells of epithelia are closely connected and are not separated by intracellular material. Three basic types of connections allow varying degrees of interaction between the cells: tight junctions, anchoring junctions, and gap junctions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Types of Cell Junctions. The three basic types of cell-to-cell junctions are tight junctions, gap junctions, and anchoring junctions.

At one end of the spectrum is the tight junction, which separates the cells into apical and basal compartments. An anchoring junction includes several types of cell junctions that help stabilize epithelial tissues. Anchoring junctions are common on the lateral and basal surfaces of cells where they provide strong and flexible connections. There are three types of anchoring junctions: desmosomes, hemidesmosomes, and adherens. Desmosomes occur in patches on the membranes of cells. The patches are structural proteins on the inner surface of the cell’s membrane. The adhesion molecule, cadherin, is embedded in these patches and projects through the cell membrane to link with the cadherin molecules of adjacent cells. These connections are especially important in holding cells together. Hemidesmosomes, which look like half a desmosome, link cells to the extracellular matrix, for example, the basal lamina. While similar in appearance to desmosomes, they include the adhesion proteins called integrins rather than cadherins. Adherens junctions use either cadherins or integrins depending on whether they are linking to other cells or matrix. The junctions are characterized by the presence of the contractile protein actin located on the cytoplasmic surface of the cell membrane. The actin can connect isolated patches or form a belt-like structure inside the cell. These junctions influence the shape and folding of the epithelial tissue.

In contrast with the tight and anchoring junctions, a gap junction forms an intercellular passageway between the membranes of adjacent cells to facilitate the movement of small molecules and ions between the cytoplasm of adjacent cells. These junctions allow electrical and metabolic coupling of adjacent cells, which coordinates function in large groups of cells.

Classification of Epithelial Tissues

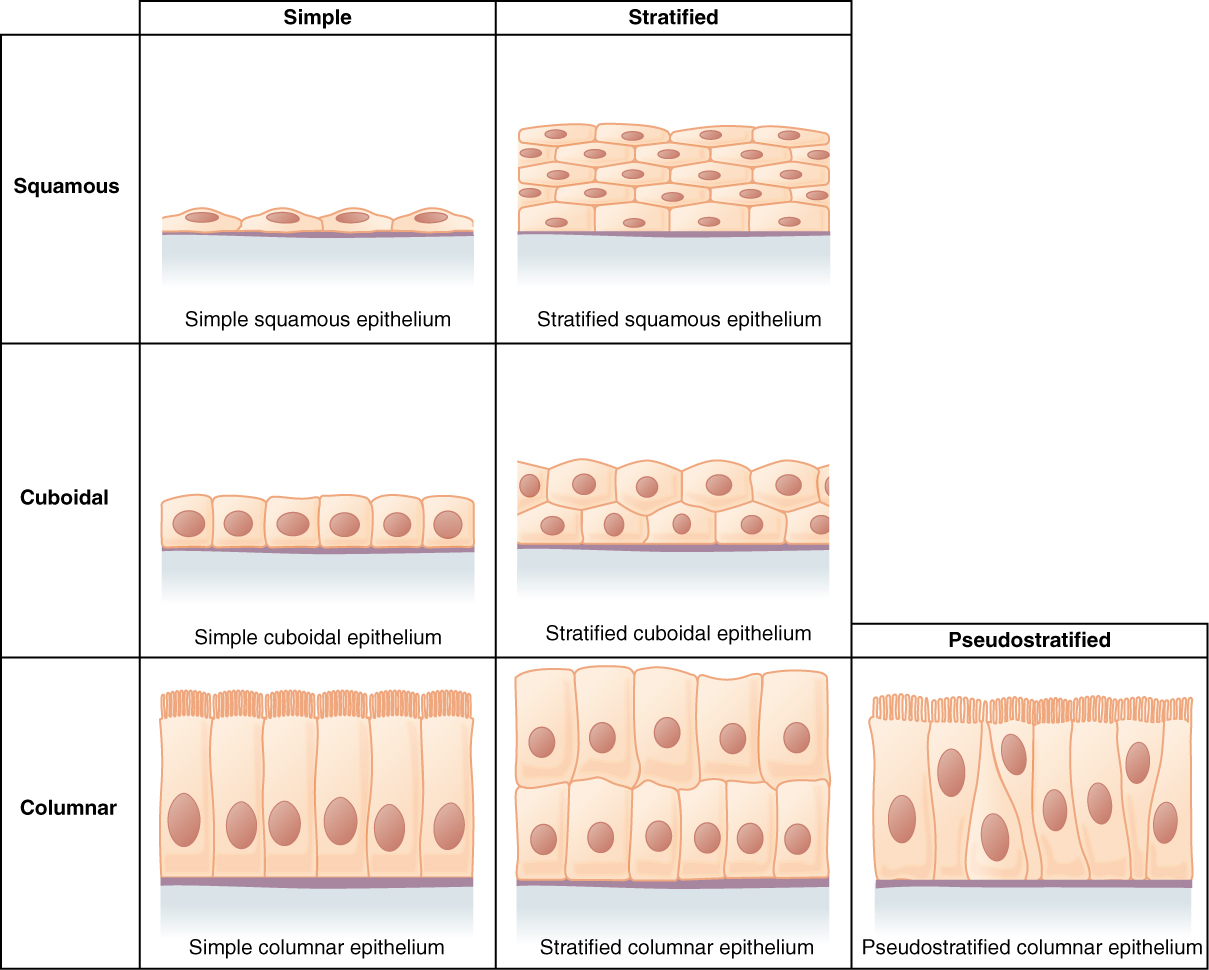

Epithelial tissues are classified according to the shape of the cells and number of the cell layers formed (Figure 2). Cell shapes can be squamous (flattened and thin), cuboidal (boxy, as wide as it is tall), or columnar (rectangular, taller than it is wide). Similarly, the number of cell layers in the tissue can be one—where every cell rests on the basal lamina—which is a simple epithelium, or more than one, which is a stratified epithelium and only the basal layer of cells rests on the basal lamina. Pseudostratified (pseudo- = “false”) describes tissue with a single layer of irregularly shaped cells that give the appearance of more than one layer. Transitional describes a form of specialized stratified epithelium in which the shape of the cells can vary.

Figure 2. Cells of Epithelial Tissue. Simple epithelial tissue is organized as a single layer of cells and stratified epithelial tissue is formed by several layers of cells.

Simple Epithelium

The shape of the cells in the single cell layer of simple epithelium reflects the functioning of those cells. The cells in simple squamous epithelium have the appearance of thin scales. Squamous cell nuclei tend to be flat, horizontal, and elliptical, mirroring the form of the cell. The endothelium is the epithelial tissue that lines vessels of the lymphatic and cardiovascular system, and it is made up of a single layer of squamous cells. Simple squamous epithelium, because of the thinness of the cell, is present where rapid passage of chemical compounds is observed. The alveoli of lungs where gases diffuse, segments of kidney tubules, and the lining of capillaries are also made of simple squamous epithelial tissue. The mesothelium is a simple squamous epithelium that forms the surface layer of the serous membrane that lines body cavities and internal organs. Its primary function is to provide a smooth and protective surface. Mesothelial cells are squamous epithelial cells that secrete a fluid that lubricates the mesothelium.

In simple cuboidal epithelium, the nucleus of the box-like cells appears round and is generally located near the center of the cell. These epithelia are active in the secretion and absorptions of molecules. Simple cuboidal epithelia are observed in the lining of the kidney tubules and in the ducts of glands.

In simple columnar epithelium, the nucleus of the tall column-like cells tends to be elongated and located in the basal end of the cells. Like the cuboidal epithelia, this epithelium is active in the absorption and secretion of molecules. Simple columnar epithelium forms the lining of some sections of the digestive system and parts of the female reproductive tract. Ciliated columnar epithelium is composed of simple columnar epithelial cells with cilia on their apical surfaces. These epithelial cells are found in the lining of the fallopian tubes and parts of the respiratory system, where the beating of the cilia helps remove particulate matter.

Pseudostratified columnar epithelium is a type of epithelium that appears to be stratified but instead consists of a single layer of irregularly shaped and differently sized columnar cells. In pseudostratified epithelium, nuclei of neighboring cells appear at different levels rather than clustered in the basal end. The arrangement gives the appearance of stratification; but in fact all the cells are in contact with the basal lamina, although some do not reach the apical surface. Pseudostratified columnar epithelium is found in the respiratory tract, where some of these cells have cilia.

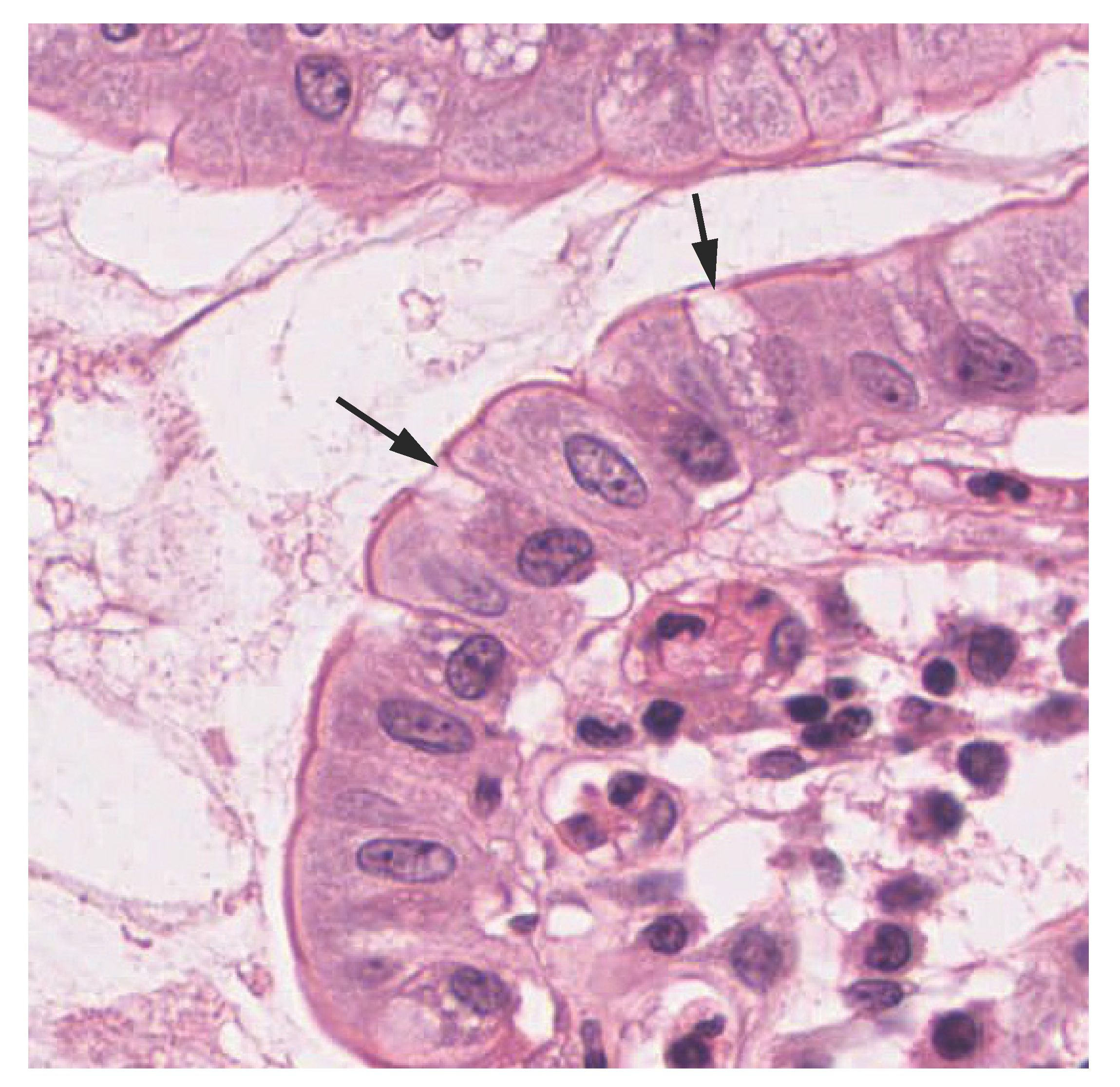

Both simple and pseudostratified columnar epithelia are heterogeneous epithelia because they include additional types of cells interspersed among the epithelial cells. For example, a goblet cellis a mucous-secreting unicellular “gland” interspersed between the columnar epithelial cells of mucous membranes (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Goblet Cell. (a) In the lining of the small intestine, columnar epithelium cells are interspersed with goblet cells. (b) The arrows in this micrograph point to the mucous-secreting goblet cells. LM × 1600. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario